上架日期:2019/4/19

臺中監獄歷史沿革

1895年(明治28年)日人治臺,開啟了長達五十年的殖民歲月。該年12月,控管中部地區的「臺灣民政支部」,擇定清領時期「臺灣府城儒考棚(今臺中州廳一帶)」做為辦公處所,將行政中心由彰化遷至臺中。

隨著臺灣民政支部的遷入,各行政機關陸續利用原考棚建物,設置單位辦公處所,其中主管衛生、警察與獄政等業務的第三課,亦改建考棚建物設置監獄(今市府路與民生路交叉口一帶),成為臺中監獄的發軔。

1896年(明治29年)3月,臺灣民政支部改制為臺中縣,監獄也更名為臺中監獄署。此時,由於中部地區臺人義軍(日人蔑稱為「土匪」)仍以武裝游擊抗日,日人掃蕩捕獲的俘虜眾多,再加上日常刑事、民事人犯,考棚改建的監獄格局過小,空間不敷使用,遂配合都市計劃,規劃將監獄遷往城郊。[1]

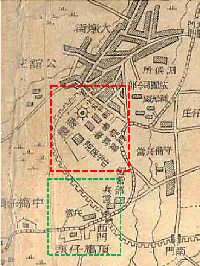

第二代監獄的位置,幾經都市計劃討論修改,最終擇定原臺灣府城西門外的砲兵軍營做為新址,並於1899年(明治32年)10月,動工新建監獄館舍。西門外的軍營,早在清領時期便是駐軍的兵營,日人接收後仍做為軍營使用,由於地處城郊,對城市發展影響較小,而部分建地屬於公有地(軍營),可降低土地徵收成本,又與臺中地方法院配套規劃,兩個業務相關單位緊鄰配置,均為臺中監獄選址的重要考量因素。

1900年(明治33年),全臺監獄改隸屬臺灣總督府管轄,臺中監獄署遂改名臺中監獄。工程期間因砲兵軍營拆除工程延宕,致使臺中監獄營建工程進度落後,整體工程一直到1903年(明治36年)3月才竣工。新完成的臺中監獄,整體範圍呈五角型,內含事務所、拘置監(判刑未決者監房)、懲役監(判刑確定者監房)、女監、工廠、炊事房等設施。1924年(大正13年)1月,臺中監獄因配合監獄官制改正,改稱臺中刑務所。此後監獄館舍雖有增改建,如新設教誨室、擴大工廠範圍等等,但格局大抵沒有太大變化。

1945年終戰後,隨著國府接收,監獄改稱「臺中第二監獄」,隔年又易稱為「臺中監獄」,主要以收容重刑及普通累、再犯受刑人為主。1980年代,臺中發展迅速,隨著城區大幅外擴,原位於城郊的臺中監獄,其位置轉而成為市中心範疇。隨著市區日漸繁榮,臺中監獄佔地阻礙發展的抨擊日起,再加上日治遺留監獄館舍老舊,整理維護成本甚高,故遷移新建的呼聲湧現。有鑑於此,法務部於1985年,於大肚山臺地上購地興建新臺中監獄、女子監獄、戒治所及看守所,並於1992年正式遷移至此,結束了第二代臺中監獄的歷史。

臺中監獄館舍拆除後,泰半改為光明國中校地。監獄相關遺留,主要為周邊附屬設施,計有臺中刑務所宿舍群、典獄長官舍與演武場等。其中,演武場已成為臺中舊城區著名景點,而整修中的典獄長官舍,待完工開放後,也將是臺中重要的歷史文化景點。

臺中監獄最知名的受刑人:蔡惠如

若細究臺中監獄歷史,其中最知名的受刑人,當屬蔡惠如無誤。蔡惠如(1881-1929),名江柳,字惠如,號鐵生等,出身臺中清水望族。年少即接掌家族事業,從事米穀經銷,後更投資輕便鐵道、製帽、製糖等事業,為人海派公義,為臺中仕紳重要意見領袖,遂成為日人刻意懷柔籠絡的對象,於1913年(大正2年)受命出任臺中區長。

初步入政壇的蔡惠如,對日人開明統治尚有期待,於1914年(大正3年)與日本自由民權運動領導者坂垣退助及林獻堂等人籌組臺灣同化會,爭取消除日臺差別待遇。無奈,隔年同化會遭到臺灣總督府以有害公安為由強制解散,而其所經營的事業也連帶受到影響導致鉅額欠債。蔡惠如因而徹底看破殖民統治歧視臺人之本質,憤而辭退一切公職,投身臺灣民族運動,並將工商經營重心移往中國,在福州開辦拓墾、漁獲等事業。

積極為臺灣民族運動奔走的蔡惠如,1920年(大正9年)在東京與臺灣留學生共創新民會,自願退居副會長職務,並邀請林獻堂出任會長。1921年(大正10年),新民會開始推動「臺灣議會設置請願運動」,以向日本帝國議會遞交臺人連署請願書的方式,要求設置臺灣議會,將臺灣總督府的立法權交還給臺灣人民。

由於「臺灣議會設置請願運動」每年推動連署遞件,逐漸累積大量民氣,引發臺灣總督府不滿。為打壓臺人民族運動,在1923年(大正12年)12月16日,發動全島性搜捕,逮捕41人、傳訊58人,引發社會恐慌與譁然,由於逮捕行動是以違反《治安警察法》為由,故事件史稱「治警事件」。

身為「臺灣議會設置請願運動」要角的蔡惠如,亦在逮捕之列。12月16日被捕後先送臺中監獄羈押,24日後再押送臺北監獄拘留問訊取供,至隔年年初方被釋放。此後歷經三次審判,於1925年(大正14年)2月判刑確定,得再入臺中監獄服刑3個月。由於臺灣總督府大動作的搜捕與審判,臺灣社會極其關注事件發展動態,隨著被捕者在法庭上慷慨激昂爭取民權的言論見諸報導,被捕受難者均被視為英雄人物,反而激起更強烈的民族運動風潮。

蔡惠如於該年2月21日,由清水自宅出發乘火車到臺中監獄報到服刑,自出家門沿途群眾佇立奉送,更有約二百人一路隨行送蔡惠如到清水車站,此後沿途各站均有人前來送行,到達臺中,車站外更是人群無數,甚至不停燃放鞭炮以示歡迎。聚集的人潮引來警察驅趕,但熱情民眾堅持不肯散去,隨著蔡惠如的緩步前行,甚至沿街形成人牆,爭睹蔡惠如風采。

離開火車站的蔡惠如,循著新盛橋通(今中山路)前往臺中醫院,探視因肺病入院療養的同志林幼春。林亦為請願運動要角,治警事件後,同被逮捕判刑,卻因病暫緩入獄,故蔡惠如再入獄之前,特意前往探視。兩人訣別後,蔡惠如前往臺中法院檢察局報到,法院前人群眾多、團團圍住門口,不捨蔡惠如入獄,最後出動大量警察驅散人群,蔡惠如才得以進入法院報到,隨後被送入一街之隔的臺中監獄服刑。[2]

服刑期間,蔡惠如創作多首詩詞作品,闡述堅持抵抗殖民不公的心志,並紀錄獄中景況,其中尤以詞作〈意難忘〉最為著名:

意難忘 下獄之日清水臺中人士見送,途將為塞,賦此鳴謝

芳草連空,又千絲萬縷。一路垂楊,牽愁離故里。壯氣入樊籠,清水驛、滿人叢,握別到臺中。老輩青年齊見送,感慰無窮。山高水遠情長,喜民心漸醒,痛苦何妨。松筠堅節操,鐵石鑄心腸。居虎口、自雍容,眠食亦如常。記得當年文信國,千古名揚。[3]

這首詞作,描述入獄沿途鄉親英雄式歡送的景象,覺得大家能站出來,一起挺身爭取臺人權益,那自己入獄的痛苦也就不算什麼事了。接續表達自己絕不因為入獄,就改變抵抗殖民的初衷,就算在監獄中也能安居自如。最後更以文天祥事蹟自我砥礪,傳達出絕不向日人妥協的堅決態度。

蔡惠如出獄後,仍舊一心為民族運動奔走,甚至耗盡家財亦不止歇,1929年(昭和4年)因腦溢血病逝,享年49歲。其一生戮力於臺灣民族運動,並創設報紙雜誌,扶助臺灣人媒體發揮社會改造與文化振興功能,對臺灣政治運動與文化發展,有著不可磨滅的重要貢獻與歷史地位。

________________________________________

[1] 參見〈臺中刑務所沿革概要〉,《臺中刑務所刑務月報》第8卷第9號,1933年1月,原書無頁碼(於目次後一頁)。

[2] 蔡惠如入獄過程,參見〈諸氏之入監〉,《臺灣民報》,1925年3月11日,5-6版。

[3] 引自廖振富編著,《蔡惠如資料彙編與研究》,臺大出版社,2013年12月,頁70。

Taichung Prison and Cai Hui-ru

History of Taichung Prison

Taiwan became a dependency of the Empire of Japan in Meiji 28 (1895). This marked the beginning of 50 years of colonial rule. In December of that year, the Taiwan Civil Affairs Branch, which controlled the island's central region, chose the Taiwan Prefecture Examination Hall (now the area around Taichung Prefecture Hall) for their offices and relocated the administrative center of the region from Changhua to Taichung.

With the move of the Taiwan Civil Affairs Branch, various administrative agencies also started to repurpose existing examination halls by utilizing building space as their offices. Of these agencies, the Third Division which was then responsible for health, policing, and prison administration, converted the examination halls into prisonswhich would then later develop into the official Taichung Prison.

In March of Meiji 29 (1896), the Taiwan Civil Affairs Branch was reorganized into Taichung County, and the prison was renamed Taichung Prison Administration. Many Taiwanese in the central region were still resisting Japanese rule during this time and used guerrilla tactics to fight the Japanese they were referred to as tufei, or bandits, by the Japanese who raided and captured many bandits as prisoners. Added to these members of resistance held in captivity were petty criminals and civil prisoners, and the converted prisons ultimately become too small to house them all. Urban planners therefore proposed moving the prison to the more spacious suburban areas of the city.[1]

After several city planning sessions were held to discuss the prison relocation, the artillery barracks outside the west gate were selected as the second site for the prison, for which construction began in October of Meiji 32 (1899). Troops had been stationed in the barracks outside the west gate as early as the Qing Dynasty. After the Japanese gained control of the island, they also made use of the barracks. Since it was in the suburbs, it had little influence on urban development. A portion of the building and land (the barracks) was moreover government owned public property, which reduced the cost of land acquisition. Taichung District Court, whose administrative offices were already located right next to those of the Prison Administration, was also in full support of the planning and design. These were all important factors in determining the new location of Taichung Prison.

In Meiji 33 (1900), all prisons in Taiwan were placed under the jurisdiction of the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan Taichung Prison Administration was therefore renamed Taichung Prison. Due to a delay in demolishing the artillery barracks, work on prison construction was hampered. The entire project was not completed until March of Meiji 36 (1903). The newly completed Taichung Prison featured an overall pentagonal shape, containing within it administrative offices, detention cells (where those awaiting sentencing were held), prison cells (where those already sentenced were held), a women's prison, factory, kitchen, and other facilities. In January of Taisho 13 (1924), in accordance with amendments made to the prison system, Taichung Prison was renamed Taichung Penitentiary. Although the penitentiary's buildings such as the factory were renovated and enlarged, and new facilities such as the confession room added, the overall layout stayed the same.

After the end of World War II in 1945, the Nationalist government took over the island and the prison was renamed Taichung Second Prison, and again renamed the following year to its current title, Taichung Prison. The majority of prisoners are felons, non-felony recidivists, and repeat offenders. Taichung City underwent rapid development in the 1980s the substantial expansion of its downtown areas meant that Taichung Prison, originally a part of the suburbs, was now located within the confines of the city center. The increasing prosperity of the urban area meant that the prison hindered urban development. Its old Japanese-era buildings meant that maintenance costs were high as well the public therefore began petitioning for relocation and reconstruction. In response, the Ministry of Justice purchased land on Dadu Plateau in 1985 and construction began on a new Taichung Prison, women's prison, rehabilitation institution, and detention center. In 1992 the prison formerly relocated, closing the books on the second Taichung Prison site.

After the old prison was demolished, most of the land became campus grounds for Taichung Kuang-Ming Junior High School. The prison's legacy has been preserved in the shape of its auxiliary buildings, such as the Taichung Penitentiary dormitories, prison warden residence, and martial arts hall. The martial arts hall has become a famous attraction in Taichung's old city area. The warden's residence, now under renovation, is also set to become an important historical and cultural attraction once work is completed and the site is open to visitors.

Taichung Prison's most famous prisoner: Cai Hui-ru

A closer look at the history of Taichung Prison will inevitably reveal the story of one of its most famous prisoners, Cai Hui-ru. Cai Hui-ru (1881-1929), given name Jiang-liu, courtesy name Hui-ru, style name Tie-sheng, was born into a prominent family in Taichung's Qingshui area. At a young age, Cai took over the family business of trading rice and grains. He also invested in other businesses such as light rail, hat making, and sugar refining. Cai was a generous and righteous man who was an important opinion leader among Taichung's gentry. This made him a target for the Japanese, who tried to win him over by appointing him Taichung's district chief in Taisho 2 (1913).

Upon initial entry into the political arena, Cai had high hopes for enlightened Japanese rule. In Taisho 3 (1914) Cai teamed up with Itagaki Taisuke and Lin Xian-tang, proponents of Japan's Freedom and People's Rights Movement, to form the Taiwan Doukakai (Taiwan Assimilation Association) to fight for the elimination of discrimination against Taiwanese. Alas, in the following year the Doukakai was arbitrarily dissolved by the Office of the Governor-General, which cited a threat to public security. Cai's businesses were also affected and huge debts were incurred. This experience enabled Cai to better see through Japanese pretenses and the depths of their discrimination against the Taiwanese people. He angrily resigned from public office and joined the national movement in Taiwan. Cai also shifted the focus of his operations to China and opened land cultivation and fishing businesses there.

Working tirelessly for Taiwan's nationalist movement, Cai founded the New People Society in Taisho 9 (1920) with Taiwanese students in Tokyo. Cai voluntarily relegated himself to the role of vice president and invited Lin Xian-tang to be president. In Taisho 10 (1921), the New People Society began to promote the Petition Movement for the Establishment of a Taiwanese Parliament and submitted petitions to the Imperial Diet of Japan calling for the establishment of a self-governing parliament and the return of legislative power from the governor's-general office back to the Taiwanese people.

The movement promoted the signing and delivery of petitions every year and gradually accumulated a large amount of popular support, triggering the displeasure of the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan. In order to suppress the nationalist movement, on December 16 of Taisho 12 (1923), the governor-general's office launched an island-wide raid, arresting 41 people and summoning 58 more, triggering great social panic and uproar. Since the arrests were made in violation of the Peace Police Act, this chain of events came to be referred to as the Peace Act Incident.

As a key player in the Petition Movement for the Establishment of a Taiwanese Parliament, Cai was one of those arrested. After his arrest on December 16, Cai was placed under police custody in Taichung Prison. He was escorted to Taipei Prison on the 24th for questioning and detained he was not released until the beginning of the following year. After three trials, Cai was found guilty in February of Taisho 14 (1925) and sentenced to three months in Taichung Prison. The arrests and trials conducted by the Office of the Governor-General shocked Taiwanese society, and members of the public followed the developments closely. As reports of the arrest of those speaking passionately for civil rights were made public, the victims of the arrest were all viewed as heroes and the nationalist movement gained even more momentum.

Cai Hui-rui left his house in Qingshui on February 21, 1925 to travel by train to Taichung Prison in order to serve his prison sentence. Stepping out the door of his home he was greeted by crowds of people. Approximately 200 people saw him off all the way to Qingshui Station others would join them at every stop along the way. When Cai arrived in Taichung, he was greeted by another massive crowd waiting outside the station that set off firecrackers as a welcoming gesture. The gathering crowds attracted the attention of the police who tried to disperse them, but the enthusiastic crowd refused to leave and moved slowly with Cai. Walls of people even formed along the street to get a glimpse of their hero.

Upon leaving the train station, Cai traveled along Shinseibashi-douri (now Zhongshan Road) to Taichung Hospital to visit Lin You-chun, a compatriot who had been hospitalized for lung disease. As another key player in the petition movement, Lin had also been arrested and sentenced, but his sentence was suspended due to his illness. It was for this reason that Cai made a special visit right before his own incarceration. After the two bid each other farewell, Cai reported to the Taichung District Prosecutor's Office. In front of the court was another crowd which, unwilling to see Cai jailed, formed a human barricade in front of the doors. A large number of police officers were deployed to disperse the crowd, and Cai was finally able to enter. He was taken to Taichung Prison, just across the street.[2]

During his imprisonment, Cai wrote many poems and lyric poems expounding his unwavering will to fight against colonial injustice and recording the conditions he experienced in prison. His lyric poem “Ode to Enduring Memories” (Yi Nan Wang) is his most famous piece of verse:

Ode to Enduring Memories

—In honor of the good folks of Qingshui, Taichung, who had gathered and amassed to bid me farewell on my day of incarceration

Verdant plains extend toward the horizon, each blade of grass intricately bound and connected. My head bows with the drooping willows as I intensely grieve this departure from my home. Valiant and impassioned, I am prepared to be incarcerated—only to be greeted by the masses at Qingshui Station, waiting to bid me farewell. One by one their hands I held, until the train’s arrival in Taichung. Old and young, these kindly faces bestow upon me infinite joy and comfort. By witness of the soaring mountains and flowing rivers, we hold each other close to our hearts. In comparison with my elation of seeing the people awakened, the pain I suffer is but trivial and insignificant. Just as evergreens stand indomitable and the bamboo signifies integrity, I shall persevere with a heart of steel and a will of stone. In these times of danger, I shall remain unperturbed, and partake of repast and slumber in unwavering tranquility. Remember the righteous patriotism of the Duke of Xinguo remember his enduring name and heroic resolution.

The poem describes the scene Cai saw on his way to prison. If every person can stand up and fight for the rights and interests of the Taiwanese people, then the pain and suffering of his time in prison would have been inconsequential. It continues on to point out that the author will not change his intentions to resist colonialism because of his imprisonment and that he is at peace even inside a jail cell. He ends by invoking Wen Tianxing's exploits for encouragement and inspiration, conveying his firm conviction of never compromising with the Japanese.

After his release from prison Cai continued to work tirelessly for the nationalist cause, not stopping even though he had run through his entire fortune. In Showa 4 (1929), Cai suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died he was 49. Cai Hui-ru had dedicated his life to the national movement in Taiwan, founding newspapers and magazines to help Taiwan's media reform society and revitalize national culture. His importance in history and his contributions to Taiwan's political movement and cultural development are indelible.

________________________________________

[1] See "Summary of the History of Taichung Penitentiary", Taichung Penitentiary Criminal Affairs Monthly Vol. 8, No. 9. January 1933. Original book had no page numbers (article is located directly after the page of contents).

[2] For more on Cai Hui-rui's imprisonment process that day, see "The Jailings", Taiwan People's News, March 11, 1925, p. 5-6.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LINE

LINE